November 11, 2016

Note on maps: I copy these off of Google Earth but they may not be the best quality. On a touch screen you can zoom in for better resolution but I’m not sure how well they work otherwise. I’ll try and evolve a better system as time goes.

Weather in Cuzco was generally rainy and cool. With a late start the day I left I only made about 30 miles for the day and pitched the tent in the rain near some roadside Inca ruins. Over the next two days the road gradually climbed to over 13,000 feet from Cuzco’s 11,200 feet, a minor grade in comparison with the previous weeks. Near the high point at Abra la Raya, 17,000+ foot peaks to the north were visible that were free of glaciers, accessible from the road and hike-able. I saw them from the bus in 2007 and remember wishing for independent travel to check them out. Having it now, I decided to take a day and climb one.

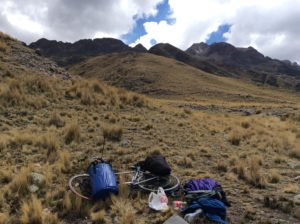

Once again, hiking legs are different from cycling legs and it was a long haul to get up there. 17,000 is still out of my acclimation zone. Great day though. A couple of afternoon thunder storms needed to be waited out and they left the peaks in a shroud of graupel. As I got higher into a cirque below the objective peaks I got fooled as to which was the highest and ended up on one about 500 feet lower than I could have gone. A beautiful sumit none-the-less. Not a hint of a trail or any tracks to the top, but there was a summit cairn.

Continuing to Puno I stopped at the Hotel Europa where Laurel and I had stayed in 2007. We were there for a few days while we explored islands on Titicaca but when we left for good I managed to leave my passport in the room. Gregorio, the hotel owner, tracked me several blocks to the bus station, and as I boarded the bus, returned it to me. There was no time for anything but “thanks a lot”. Well, I found Gregorio still there after ten years and he remembered me. I gave him a long overdue twenty bucks reward that should have been more like a hundred.

After Puno roads narrowed but traffic remained fairly lite. At the Bolivian border I got hit with a load of beauracracy as Bolivia now requires a visa for USA visitors and charges $160. It took two days to get through it all. Minutia, like getting visa photos and requiring payment in US cash (with bills in perfect condition), made for many trips back and forth to the Peru side. There are two entities of Bolivian gov’t at the border; military and migration. Oddly enough, the military folks were observing it all and actually went to bat for me against what migration was putting me through. When one US $20 bill had a small tear in it they were saying it was ridiculous to go back to Peru just to get another one. Unfortunately, migration usually trumped but the military guys always made sure I skipped standing in line again each time I came back. The last straw was a requirement that I had to have hotel reservations lined up during my stay for which the military folks simply called bullshit- I didn’t get the conversation word-for-word but the gist was “this guy’s on a bicycle and many Bolivian distances between towns & hotels cannot be covered realistically in one day.” The guards won that one for me.

I have to add as well that after all the warnings about Latin American police and military corruption- things like having drugs planted on you and then coercing a bribe to go free or people posing as police and then robbing you- I have found none of it. I can’t judge what goes on in their internal affairs, but I have found both police and military in Latin America helpfull and friendly throughout. In another volume I’ll recall some tales.

Both Chile and Argentina recently were also charging a $160 fee to US tourists, as well as the US charging a similar reciprocity fee. Where the number 160 came from is anybody’s guess, but a recent visit by Obama to Argentina resulted in a waiver of fees from both sides. Chile soon followed suit but Bolivia has held out. I can’t say I blame them, they are South America’s poorest nation and tourism isn’t as prosperous as in neighboring countries. They are landlocked, the result of a war with Chile in the late 1800s over mining claims for extracting sodium nitrate. Sodium nitrate, or saltpeter, was used for making gun powder and explosives. Bird guano, found on the coasts, also had a sizable market back then for fertilizer. Peru and Bolivia allied against Chile in what became “The War of the Pacific” but Chile had greater financial backing from the mining interests and ended up winning the Bolivian port of Antofagasta and Peru’s port of Arica. In recent times, Chile has been generous to Bolivia with port fees and duties but Bolivia is still landlocked and it requires an ascent of 13,000 feet to reach its western border from the port of Arica. They also lost territory to Paraguay in the Chaco war which took place in the 1930s.

On the up side, Bolivia has realized natural gas potential in recent years and has income today from providing northern Argentina with natural gas and propane. Argentina also hires Bolivian labor which, for better or worse, channels money to the country. They’re also South America’s largest grower of coca, but much of it is for domestic use and legal. It should be pointed out that coca leaves made into tea has less of a narcotic effect than caffeine or even sugar. This is how the natives use it today and how they’ve used it for centuries. Cocaine is the result of many intricate distillations of coca leaves. Some of Bolivia’s coca, though, does make it into black markets for cocaine.

Entering Bolivia started out as continuation around Lake Titicaca but then climbed over low hills to La Paz. A city of 2 million people, I avoided going into La Paz proper but had a hard time navigating roads that would avoid it. Many were dirt or cobblestone and involved crossing streams, one of which was pretty much sewage. The roads emanate radially from the center La Paz and I was coming out almost in the opposite direction from coming in, so it wasn’t very far jumping across, but it took the better part of a day.

Agricultural land at 12,000 feet surrounds La Paz to the west and south, but gives way to a barren network a badlands and playa as Oruro is approached. Soon the playa flats become the pure salt of the Salar de Uyuni, the world’s largest salt flat. Bolivia is trying to develope the town of Uyuni for tourism with an airport, hotels, restaurants and tours. I didn’t see any North Americans but there were a few Europeans in Uyuni.

The highway to Uyuni from Oruro was newly paved, had a wide shoulder and very little traffic. Both maps and people I talked to indicated paved road continued from Uyuni to the town of Tupiza near the Argentine border. Such was not the case. In Uyuni, I found Wi-Fi and spent some time on Google Earth where I can zoom in on highways and see if there’s a white stripe- a sure indicator of pavement. However, even without the stripe, a road still might be paved if the satellite image predates paving. That’s happened a couple of times. In this case, though, the 120 miles to Tupiza was going to be mostly dirt. It turns out they are in the process of paving it and had maybe 20 miles total completed and another 10 or so where it had been “rolled smooth” just prior to paving. The rest was either washboard, rock, or deep sand requiring getting off the bike and pushing. There was maybe ten miles of the latter. My rear tire was fairly warn and a little smaller than what I usually try to find- a “23c” width as opposed to a “25c”. I found a very good quality Specialized 25c in Bogotá that I got an unprecedented 2000 miles out of and no flats till the tire was essentially warn out. Unfortunately, I hadn’t seen a 25c tire since then. The 23c meant a few flats and then many more from Latin American patch kits that just don’t hold up that well. Bumpy roads and high pressure seems to shorten the life of the patches and you end up putting a patch on top of a patch, and so on, till there are four or five patches covering one leak. I’ve tried switching glue to what the the automotive shops use, but it didn’t seem to make a difference. Regardless, I was on a loaded road bike treading into the domain of mountain bikes.

Once again, the flat tires, the wind, dust, hills, rough road, were all offset by incredible country and great camps. It took four days (three nights) and I had just enough food with an addition of apples and candy bars from generous Bolivians passing by towards the end. The route follows a rail line and water was available at small communities associated with the railroad. Also, there is a mining town, Atocha, at about the halfway point that offered some resupply.

The last leg into Tupiza was a long descent down a washboard road that had many crossings of a small stream. Tupiza itself is a sizable town of 25,000 situated in a verdant valley lined with red rock foothills and cliffs. It’s a sort of Bolivian version of Moab and has a similar climate. They’re working on the tourism. I laid over there two nights and did a thorough cleaning of the bike. That involves many syringe fulls of raw gas injected into the oil journals of the hubs as well as pouring gasoline down the seat tube to rinse sand out of the bottom bracket. The derailleurs are cleaned with a toothbrush and gas. New oil is added the same way. It’s akin to an “oil change” that I do every couple of months or after prolonged riding in sand or rain.

Crossing into Argentina required no lines and was free. They did run my bags through an outdoor x-ray scan, but that was it. It was Sunday and there wasn’t much open but I found an ATM (Cajera) and then a small grocery store with enough supplies for a dinner and breakfast. Then I rode out into a very remote corner of Argentina, more sparsely populated than just across the border in Bolivia. Far more llama husbandry here, and in Bolivia as well, than in Peru. Had some tailwind, but riding the Altiplano winds come from all directions. Mornings usually start calm and morning frost gives way to wearing a tee shirt and shorts by mid morning. By early afternoon, however, the winds would pick up and it seemed about 50/50 that I’d get a tailwind. By late afternoon I’d be bundled up for winter again and looking for a sheltered spot to camp. One day was especially bad where there was dust from a ten mile stretch of construction.

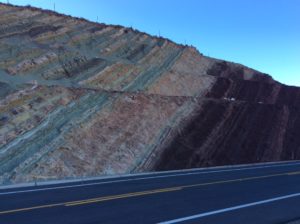

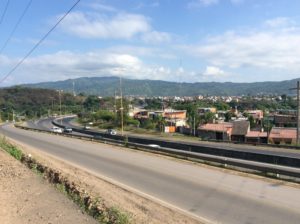

I had a choice of more dirt road heading over a 17,500 foot pass or a drop from the 12,000 foot Altiplano to the towns of Jujuy and Salta, which are at 4000 feet, followed then by a climb again to a somewhat lower Altiplano. I took the latter and I’m in Salta now. It’s verdantly green and very modern though the no-shouldered, busy autopista from Jujuy to Salta was as dangerous as anything I’d seen since Mexico. There was a back road over a pass that connected the two, but I let a guy at a bike shop talk me out of it. The tuktuks and motor cycles of cities in Peru and Bolivia are SUVs and buses in Argentina. I had dinner last night in a crowded plein air restaurant in the main plaza that could have been downtown Paris. I ended up having a long conversation with an Irish couple, Frank and Vivian, sitting at the next table.

Tomorrow I start for Mendoza and will hopefully be there in a couple of weeks. There appears to be more Utah-like terrain ahead, this time at a lower elevation that I hope isn’t too hot. Salta’s been a refreshing rest from the windswept Altiplano, but I’ll be glad to get back to desert quiet. I’ve logged several 100+ mile days since Cuzco and should get a few more in the next leg if the winds treat me right. It’s starting to go very fast now.