April 24, 2017

Getting away from Lusaka was a challenge. The morning I was to leave, Luis set me up with his video camera that he mounted on the handlebars to get footage riding from his place to a café near downtown where he bought me breakfast. A bike cam is something I should have probably had all along to catalogue some of the riding, and I may buy one yet if I’m ever in one pace long enough to shop for one. At the café the loaded bike soon attracted a crowd in the parking lot with every one wanting to know details. One lady, Brenda, gave me a 50 kwacha donation (about $5) and soon she and her daughter and a couple of other folks were all being treated to breakfast by Luis at the café.

As we talked in the café- in an English I would struggle to understand even if my hearing were 100 percent- we learned that Brenda was running a school for underprivileged children at her house in Chilanga, a town 10 miles south of Lusaka. She mentioned also some horrible murders going on in her neighborhood where two children were killed and then internal organs removed in a sort of witchcraft sorcery. Things aren’t what they seem in otherwise happy and peaceful Lusaka. After we had talked I decided to go and take a look at what she was doing with the intent I could pass the info on to people that might be able to help her financially.

She and her family are farely well to do as far as Zambians go, her husband being an electrical engineer spending most of his time in South Africa. They own about three acres of land where they’re building three more rental houses on their property. Short on funds, the building came to a stop, but she now wants to use at least one of the houses for the school. She said that since the murders, children from more or less good family situations are now staying home because it’s safer; children from not so good family situations are coming to her place for the same reason- safety. Lack of education and illiteracy are high in Zambia. There is a pubic school system but it is not necessarily well attended. I don’t have demographic details but it would be interesting to know.

I ended up staying the night with Brenda, Niza and their family and was again treated like royalty. They walked with me the next morning a kilometer to the main highway and we had a long goodby in company with several neighbors.

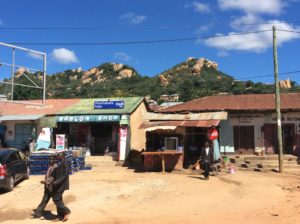

North of Lusaka the main highway continues to copper belt areas and on to Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Due to revenues from extractive industries things are fairly modern along this route and most ammenities can be found. I turned off of it however a hundred miles to the north of Lusaka and travelled into Zambia’s more remote northestern district which is much poorer. The modern grocery stores of Lusaka became shops selling grains and a few can goods. Coke and Pepsi although are found throughout. Fruits and veggies could still be found at roadside stands and through it all I was able to eat OK, just no Reggianno cheese or red wine with pasta. On the positive side, things were very cheap and I was getting by on a couple of dollars a day. Camping was relatively easy.

One rainy day I had the bike bags well bundled up, but jettisoned the raincoat, stored the wallet, and in shorts and Tevas just got wet. But it wasn’t that warm and I spent an afternoon borderline shivering. A couple of days later I had the flu. I rode for two more days to Mpika and actually found a good hotel and after a day resting felt like I was improving enough to start on a two hundred mile stretch to Isoka. Then it really hit me. I was in about the seventh day of riding sick when I found a clinic in the small villiage of Matumbo. I was wondering if I had Malaria but the nurse there, Peter, tested for it and it came up negative. The symptoms seemed more bacterial than viral and I decided to chance antibiotics which Peter gave me along with more Malaria test kits, pain relievers and antihistamines. I gave him about half the cash I had on hand which amounted to about $10. The antibiotic did the trick and I was feeling better after a couple of days. Having to keep riding through it all was tough.

At the clinic “office” they had charts on a wall that kept track of individual patients and it was telling to see the amount of Malaria and HIV patients. Both are a major problem in Central Africa.

Northern Zambia is very poor and there are children everywhere. They line the roads, some going to and from school, others just hanging out. Teenaged mothers are routinely seen carrying infants. The kids can be a problem and constantly beg. They will start out with how are you or good morning (at any time of the day) and then say money or give me money or give me my money and I even heard give me back my money a couple of times. I could go for weeks without seeing a white person, so for them to see a white apparition on a bicycle ride by is cause for great excitement. If I was on flat terrain and had good speed I could say hi back or just ingnore them and keep going, all the while hearing how are you, I’m fine and money till I was out of earshot. If I was going up hill, though, they would run along side and be grabbing at the bike along with the heckling. It gave one visions of Gulliver’s Travels.

I got to the border with Tanzania and crossed fairly easily but got my first dose of Tanzanian begging and money extortion. It leaves Zambia in the dust. Any border will be replete with money changers that are all over you to exchange currency. I try to spend as much of one country’s cash as I can before getting to a border because your not going to get a good exchange rate in the first place and they’re going to short change you in the second place. If it’s just a few dollars I don’t worry about it and accept the forfeiture. At the Tanzanian border I had maybe $40 in Kwacha but knew there would be visa fees to spend it on. Immigration first said it was $50 but it had to be in greenbacks. There was a place a few doors down that would dispence dollars, but in going there I was being hounded by a smartly dressed guy in white shoes that wanted me to do the exchange with him. I told him any left over kwats would go to him. Since I didn’t have $50 in Zambian Kwacha I had to get an ATM and then swap for a crisp new US $50 at the exchange office. When I got back to immigration, the officer said he hadn’t noticed I was American and said it would be another $50. Then, in the same breath added that I could still do it for the original $50 but it would only be good for 14 days and said it would be tough to make Kenya that quickly on the bicycle. He added it was good for one year and multiple entries and mentioned other added bonuses I was by that time not paying attention to. It was like buying a phone plan. I figured better safe than sorry and headed back to the exchange office. Of course, my white-shoed friend was waiting with a $50 in his hand. What ever. I still had Kwachas to get rid of so we did the deal. I got the magic STAMP and was on my way. But then Mr White Shoes says as I’m walking out the door that he had miscalculated and needed another 10,000 Shillings (a few dollars) and I gave it to him. But I made the mistake of letting him see the juicy stack of shillings still in my wallet and with hardly a studder he said he needed still more. At this point we went back in the immigration office and I got out a pen and on the back of a blank visa form started to hand calculate what the exchange should be. He distracted me the whole time, saying things like he could do all this easily on his calculator, but I made him wait and said the more he talked the longer this was going to take. Once satisfied he’d already gotten a good deal, I told him I wasn’t paying anything more. Then he said he would go to the police. At that I said, yes, lets go to the police. It wasn’t hard to find a policeman, and though the officer said he didn’t know exchange rates, he took the original stack of bills I gave to White Shoes, put it in my hand and said to go to the exchange office and have it valued. When I got to the exchange I told the guy to just give me another $50 back, which he did along with about $10 in shillings! I walked back out to White Shoes and gave him back his $50, pocketed the $10, and left him still insisting I ripped him off as I rode away. Welcome to Tanzania.

The border of Tanzania also marked the one year point for having been on the road. The odometer was a little over 16,000 miles and I figured I was on the bike for about 300 of the days. So, I’ve averaged about 55 miles a day when riding.

I had a chance encounter in Botswana with a guy, Andrew Marx, who saw me fixing a flat on a deserted stretch while he was enroute to Pretoria. He stopped and offered to fill the tire with an electric pump which I took him up on. I mentioned some of my tire and tube woes and inquired as to what I’d find in that regard in Zambia and Tanzania. The answer was “not much”. He’s an Africaaner and working with a British mining company in Mbeya, Tanzania, a town not too far from the border with Zambia. He said he’d be returning to Mbeya (with his wife and a new baby) in a few weeks and could get tires and tubes in Pretoria which I could pick up on the way through. He didn’t ask for money but we exchanged email addresses and he drove off. I had been having trouble with tubes on the rear tire that were splitting on the inside seam and was increasingly convinced it was a combination of cheap tubes and using thinner 23c tubes on the fatter 28c tires. But the problem had been getting progressively worse and now a tube was bursting every couple of days. The rim strip, which in this case was just duck tape, looked OK, so I couldn’t imagine that being the cause. I finally made a new rim strip out of an old tube (I have many of them) and that fixed the problem. Still not sure what the actual cause was. It began happening clear back in Peru with the flats steadily increasing in frequency ever since.

In Lusaka, I bought a less than desirable tire and a couple of tubes with thicker “schrader” valves for which I had to file out the hole in the rim (meant for a “presta” tube) to fit the valve. I had pretty much forgotten about Andrew and then I got an email as I neared Mbeya that he had the tires complete with 28c tubes. He recommended a hotel there and we met up a few days later. I had a great evening at the hotel’s plein aire restaurant with six or eight of his English speaking friends also working jobs in Tanzania. I spent a couple of hours talking to a guy from Chicago who is collecting epidemiology data for the US Gov’t. First person from home I’ve seen in a while (although Chicago’s is of course a bit of a foreign country).

Added to the splitting tube fiascos have been patch kits that work poorly at best and require a sort of alchemy to get to work at all. I might bore you with all the techniques, combinations, frustrations and failures at some point when I have more time. I long for Rema Tiptop kits which I should have filled a pannier with before leaving the US. I’ll be looking for patch kits here in Nairobi before I leave.

Tanzania has been a tough country to ride through. There were some good miles after Mbeya getting to Iringa and then to Dodoma, the twin capitol with Dar es Salaam, but after that you get into Maasai territory where the children are even more aggressive beggars and often throw rocks when they don’t get their way. I haven’t been hit directly yet, but they hit the pannier once with a plum-sized rock that was thrown from atop a road cut where it gathered enough speed to have done some damage had it hit me. The Maasai are traditionally cattle herders and dress in colorful frocks called shúkàs. They set the world standard for ear piercing and stretching. They’re fiercely traditional, paternalistic and resistant to changes the modern world is bringing to their culture. They’re maintaining traditions of nomadic herding, but their populations are also increasing, helped in part by the same modern world benefits they’re fighting to reject. With the greater numbers comes more cows and with that an over-grazed range that it’s a wonder a cow can even surive on. The cows are all skin and bone.

Tanzania was a colony of sorts for the Germans beginning in the late 1800s but was lost to the British after WWI. It was governed as Tanganyika on the mainland and Zanzibar on the island archipelago. Independence was gained from the British in 1961 and thence renamed Tanzania, a combination of the two disricts. You hear two pronunciations depending on who your talking to, Tan-zan-‘ia or Tan-‘zan-ia.

After independence it was voted to make a unifying language of the 104 recognized languages the country embraces (Zambia has 72). Swahili was already lingua franca for the African Great Lakes region and had become a coagulation several languages in itself, having Bantu origins but through trade had picked up other African languages as well as Arabic and Latin (meza is Swahili for table). It’s taught in the primary schools so children that go to school will be bilingual in their native tongue and Swahili. Swahili is spoken in courts of law and gov’t. The bottom line for me in all this is that few people speak English in Tanzania.

I fought my way to Arusha, which is the gateway to both the Serengeti and Mt Kilimanjaro. Things became more touristy, I began seeing white people again, and amenities like grocery stores and Wi-Fi became available. I spent a night in a hotel in Arusha and then made my way north to the border with Kenya, two days ride away.

Camping was difficult enough among the Maasai here that I went to a hotel in Longido where they had a place to pitch the tent for $10 a night, breakfast included. I met there Penny and Melanie who are doing NGO work with rural Tanzanians and focused on women’s health issues. Penny is an MD from the UK and Melanie, her daughter-in-law, was born in Kenya but lives in Vermont with her husband (a wild life photographer and film maker) and two children. It was wonderful to communicate with English speakers. The hotel itself (Hotel Tembo) has NGO funding and is set up with solar electric panels, solar hot water heaters and rooftop rainwater collection. The property is a sort of pilot project that engineering students are participating in. There was a paper in a loose leaf binder in the hotel commons that was set in an academic tone, and described work being done there. It was fascinating to see measures to conserve water in this region with its long dry seasons. The project, Buckets to Rain Barrels is funded by Canadians. More info can be found here.

Penny and Melanie are traveling to remote villiages to provide information on prenatal care and women’s health issues. They’ve been doing this for eight years but just this year they’re walking on the eggshell terrain of subjects like planned parenthood. The culture they’re working with is steeped in a tradition where fathers receive money (cattle) from suitors when the daughter marries. The father is always eager to attain such wealth and daughters are often betrothed at 9 or 10 years old and married by their early teens. This, of course, interferes with education not to mention subjecting a girl to a life of virtual slavery. Suitors often already have wives, and a younger girl entering into such a family is often abused by wives jealous of the attentions the new wife might be getting. Education often opens the eyes of young girls subjected to this culture, and though polygamy is legal, keeping a girl from going to school that wants to do so is illegal. It’s likely these rights are not much talked about in the paternalistic society. It’s easy to imagine such misogynous fathers and husbands a few short years ago throwing rocks at passing bicyclists.

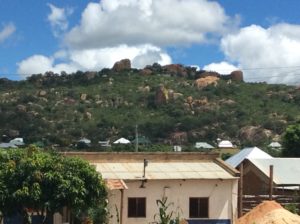

I decided to spend an extra day there and learn more. Melanie suggested a hike up the adjacent mountain the town of Longido lies next to called, not surprisingly, Mt Longido. Caroline, the hotel manager, said I couldn’t go there alone and had to have a guide. She was instantly on the phone that morning during breakfast. The guide, Juma, came by a few minutes later and said the fee was $50. I offered $20 and we agreed on $25. I had a great day. Like my friend Walter from all the way back in Costa Rica, Juma had some training in natural sciences, binomial taxonomy, and was very good with bird ID. I got my money’s worth. The hike was wonderful. Juma was something of a climber, having guided Kilimanjaro, and we did some easy 5th class scrambling to get to the summit. (I should mention as well that he said just this year they completed a mountain bike trail to the top of Kilimanjaro’s 19,300 foot summit!). Cape buffalo and elephants graze easier slopes on the far side of Mt Longido and we saw buffalo scat in rocky terrain near the summit. When we got down I gave him a tip and took him to lunch.

The work being done at the hotel had some maintenance problems, the worst of which was the roof gutters that caught the rain water. I agreed to stay an extra day and work on them. The building is an octagon shape and the gutter joints are at an odd angle. The game is to use only local materials that can be readily available to the inhabitants, so 4″ PVC pipe was spit in two for the gutters and attached with a manufactured hanger evidently sold in their small hardware shops. I found a pair of tin snips at the hotel and tried to fashion angled joints out of some metal roofing that was laying around. I bought a tube of silicone and a caulking gun at the towns hardware store. I improved things, but the system really needs a re-think. I was able to observe it in a hard rain and saw that about 70 percent of the water was shooting over the top of gutter and onto the ground. The system works well enough in the wet season but they haven’t the cistern capacity to take them very far into the dry season even if the catchment were improved. I wouldn’t call the project ill concieved, but it needs budget to work out the kinks that go with R & D.

I left Tembo the following morning and crossed into Kenya by about noon. Lots of hoops to jump through with visas and money. A $50 greenback with a defect in it sent me to the back of the line. I got some comic relief when the customs folks wanted documentation on the bicycle make and model. I pointed out first the name on my passport, then the decal on the bike’s downtube. Then the SW on on the head tube, then the SW under the bottom bracket. The coup de grace was the Steve & Walker cut into the opposing tangs on the inside of the forks. I convinced them! They wanted then to know more about the trip and the one official, Emmanuel, has even left a comment in the blog. These are all firsts.

A later encounter with a Maasai youth and his little brother at a petrol convenience store was a little tense. He came up to me demanding money with the little brother standing there grabbing at the bike. I told them both to back off. He was almost as tall as me and I would have had my hands full if it came to a fight. He wouldn’t stand down and soon we’re faced off nose-to-nose and, almost shouting, I told him to get the hell away from the bike. He finally backed down and they both disappeared.

Then there was one more money encounter that ended unfavoraby this time. I had had lunch at place with a really nice guy that served good food at a fair price. I paid using the new Kenyan shillings. It’s always a challenge adjusting to new currency, but I did it OK and felt good about the conversion from Tanzanian shillings. Later I bought a litre of water but when told the price my brain reverted to Tanzanian shillings and I was thinking 600 T. shillings when it was only 60 K. shillings. When I payed with a 1000 K. shilling note this kid saw it right off. He nonchalantly gave me 400 change and, bingo, I just payed about $6 for a litre of water. I realized the mistake as I walked out the door but didn’t do anything about it. Win some, loose some.

Easy miles then took me to a camp in the bush. I was more careful selecting a camp site than I’ve been in a while. I “egressed” the highway with no cars or people in sight and quickly got a secluded spot. Goat’s heads have been ubiquitous since entering Tanzania so the bike has to be carried any time you leave the highway. Not an easy task.

So, now I’m in Nairobi and will go to the Ethiopian Embassy tomorrow for visa stuff and continue the never ending quest for bike shops. It appears the road north to Ethiopia is now mostly paved, but it wasn’t just a few years ago. It was slated to be completed in 2016 but time will tell if it’s true. I may spend some time on Mt. Kenya if weather cooperates. Addis Ababa in Ethiopia is maybe two weeks away if I rode straight through.

–

Dear Steve,

Reading your blog gives me a interessting view on The actual live in Afrika, Thank you!

I Hope you Beated The sickness with The Roots and wisch you all The best for The remaining Trip!✌️

Daniel🇨🇭

Steve and Luis:

The video is terrific! That’s a great idea–Steve I hope you can doing more of that. Take care…

Hi Steve,

Nice to see you are progressing well!!

Here is the YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMr2JnQDjSQ&feature=youtu.be

For the video I made.

Take care, until next time!

Luis (Lusaka Host)

Hi Steve, I look forward to hearing from you, since you are out 1 year, 16,000 miles and in Africa, which I know little about! The details of your blog are compelling! It seems to me you are doing great navigating all of the challenges! I am glad you got over your sickness with the antibiotic. And got through your encounters with begging children, sad but I imagine it’s a learned survival skill….I’m glad you had the Make, Model and Serial number available on your bicycle for the authorities. 🙂 Good luck on the next leg of the journey!!