May 28, 2017

I left off the last segment with next wanting to get a visa to Ethiopia in Nairobi, Kenya. I managed to do it but there were several hurdles. Ethiopia wanted a “letter” from the US Embassy stating intentions. This meant trips on the bike across town, two more nights in hotels and more long lines to simply be given a US letterheaded sheet of paper that I hand wrote my Ethiopian itinerary on. The US Embassy then stamped it with what amounted to a notary public. It cost $50 to do that. I must say that a bicycle is the only way to get around in the horrendous Nairobi traffic- or any other African capitol I’ve yet been to.

At the Ethiopian Embassy there were never any lines to speak of, but you waited just the same. They had comfortable couches and magazines to look at and it felt more like a doctor’s office. In the end they approved the visa, all for $140. In one sense it was almost too easy; I was expecting warnings about problems at the border with Kenya, and even hoping for some free consultation on what to expect. I inquired about border violence but this woman just said “no, everything is at peace now”.

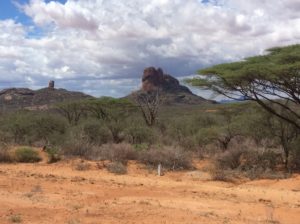

Kenya, southern Ethiopia and northwestern Somalia all meet near the town of Moyale. The border is not well defined in surrounding areas and there has been fighting in recent years. It is unclear how much is “government sponsored” and how much is intertribal. Much of the land of northern Kenya is the Chalbi Desert. It is occupied by semi-nomadic herders from many language groups and for which international boundaries are not necessarily respected. They fight among themselves and have done so for millennia. Livestock rustling is a way of life and, even today, a young man coming home with a haul of goats is just a rite to adulthood. From the perspective of a Western cyclist passing through they might be described as wild and not playing by the same rules. It made for some interesting episodes, stay tuned.

Mt Kenya lay on the route north of Nairobi. It’s highest point is a little over 17,000 feet and is the second highest mountain in Africa, next to Kilimanjaro. Unlike Kilimanjaro, a guide is not required to climb it which I was hoping would bring things into my price range. It’s also a much more interesting mountain than the Kilimanjaro volcano, with jagged spires and exposed faces reminiscent of the Tetons. The two highest summits, Bation and Nelion, are “technical” meaning the average person would want to be roped up to climb it. I was hoping to either find partners or climb sans rope if either peak looked reasonable. The third highest point is Lenana, a walk up, and the most popular summit.

So, I found a campground in the nearby tourist town of Nanyuki where I could stay and then leave the bike. A taxi took me to the trailhead. Once there I was dismayed to find a park fee of $50 a day and, though guides aren’t required in general, you must have a guide if you’re solo. A guide costs $30 a day and then there is a onetime camping fee of $20. My taxi driver was, of course, right there to line me up with a guide service and took me to the office of one back in town. Being all packed up for four days of hiking and just that close to actually doing it, I let them talk me into a hikeup of Lenana for grand total of $380. A technical climb of Bation would be $700 but they said if I felt like “3rd classing it” when I got up there I could, and the “hiking guide” would just wait for me. It’s all pretty subjective and I think the most important thing is that they get your money, although $30 a day for a guide is ridiculously cheap. The $50 and $30 fees should probably be swapped.

I still can’t decide if it was worth it or not. To make a long story short, I hiked through rainy weather to a base camp (Camp Shipton), ditched my somewhat obnoxious guide on the day of the climb, and hiked to the top of a snow dusted Lenana. The next day I hiked out. Saw lots of new birds, Zebras and Cape Buffalo lower down as well as incredible flora in the alpine. The pictures say it all.

Mt Kenya was a fair amount of work, but it was a nice break from cycling. It felt good to get back on the bike. The next miles went through small towns populated with Meru speakers. These folks are friendly, have more of a Westernized economy (for better or worse) and English speakers are common. I stopped to buy tomatoes that were being sold from the trunk of a car and ended up camping at the house of the seller, Josephat. He and his family were hospitable and brought out chai tea to drink in the evening. We talked well into the night about anything and everything. Many Africans, these folks included, are aware of advances in the world of genetics and have at least a glimmer of understanding (as much as me, anyway) regarding recent discoveries in the world of mitochondrial DNA, i.e., we all come from Africa and, more specifically, all trans African humanity has a common African “grand mother” that dates to a short 80,000-100,000 years ago. White skin is a recent developement that amounts to infinitesimally small differences in the human genome. It was gratifying to talk about this stuff with native Africans.

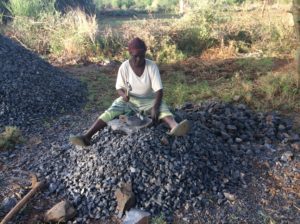

At the town of Isiola you leave Meru speakers and enter the domain of semi-nomadic pastoralists. The culture is similar to the Maasai and many come from the same basic language group, Nilotic, but are comprised of many different tribes including Samburu, Turkanas, Rendille, Gabbra, Somali, Bomba, Kikuyu, Luo to name a few. As I got close to some of the camps a guy in a Land Rover was coming towards me and stopped to talk. I was already leary of such behavior out on these deserted roads, but this guy seemed OK. He was from the pastoral culture and had the characteristic stretched ears but the fact he was driving an automobile means he also had a connection to Western culture- he wasn’t going to mess with me. Sure enough, he told me when I saw these camps and herders along the road side to just keep moving. Sound advice. The first few encounters were just the usual begging but then a few became more aggressive. These weren’t children anymore, more like twenty year olds. On one uphill a guy ran behind me and pulled the bike to a stop and demanded money. I told him no and started to ride off and he pulled the bike to a stop again. I told him NO again and waved him to get back and he let me go. I had a can of bear spray in the front pack but it wasn’t readily available. I would have used it otherwise, but I’m glad I didn’t. With time to think about it, I decided it would just make things worse unless I really feared for my life. As primitive as these guys are, the one 21st century commodity I sometimes see is a cell phone; he would have just called ahead to relatives. (As a foot note, I have this image of these two Maasai herders back in Tanzania decked out in their crimson finery, walking in tandem with a bunch of cows ahead of them. Each had the stick they use as a cattle prod tucked under an arm, then each had one hand holding a cell phone, the other shading the screen so they could see to text. Would have made a great adverisement for iPhone). Anyway, that was the first guy. Then it happened again. This time the bear spray was right there, but this “kid”, dressed in a bright blue shúkà and a good 3 or 4 inches taller than me, let me go the first time. Others waved me to stop, but I was on flatter ground and could go around and then outrun them. That happened several times over the next couple of days.

A long ways from any towns, there was no choice but to camp as evening came on. This actually wasn’t too bad. I’d hit a section where there were no people in sight and get the bike off the road and into the bush unnoticed. Then I’d just hang for a few minutes. If anybody did see me, they’d be right over and I’d march back to the highway. Next, I’d take a short hike around and look for tracks, livestock or human, and any well used paths. You listen for the bells that hang on the cows. Jackasses make a loud bray. If you get a green light on all that, camp. It’s really no different than a camp anywhere, just here, if somebody did find you with all your stuff unloaded and scattered around, you’d be robbed for sure.

The next day was more of the same. Flat-to-downhill, terrain made outrunning easier, but when there was a chase it always left you unnerved. I came to a small village called Log-Logo, got water at a grocery store and began a long grade to the town of Marsabit. I knew I was going to get harassed on the uphill and after a mile or two came to a military looking installation and pulled in. Two guys in a small pickup truck, David Ndundo and Mathew Geacho, were pulling out and pretty much new what was going on. They loaded the bike into the back of the truck and took me 10 miles to a hotel in Marsabit.

I spent the night there and the next morning found a van that was going to Moyale, the border town with Ethiopia. It was about a 150 mile ride that passed through many herder communities. I was glad I didn’t try to cycle it.

By comparison of cultures, over the endless expanses of Patagonia, the perspective of an Argentine driving along and seeing a lone bicycle is “how’s this guy surviving out here in the middle of nowhere? I’ll see if he needs help”. For a Chalbi Desert herder in the middle of nowhere it’s more like “how come this guy gets the luxury of a bicycle loaded with more stuff than we’re going to see in a lifetime? Lets check him out a little closer”. From there it becomes a game taking intimidation begging to the limit of outright robbery, a line that I’m sure gets crossed. It gives you some idea what it must have been like for a white man to roam the American west in the 1800s.

At Moyale I was immediately swarmed with people as I unloaded the bike from the van’s roof. Everybody wanted to do something for me that would get them a tip. I was becoming more and more annoyed as I repacked the bike and one guy finally cleared everybody away. I was thankful till I realized he just wanted me for himself. Once the bike was loaded I could ride away, hopefully with all my gear still intact. Then it was the same drill of getting checked out of one country and into another. The money changers were waiting and I had about a hundred dollars worth to change out. This time I was ready for them. I had ample time in the van to calculate how much Ethiopian birr I should get, and got them in a bidding war, exploiting rivalries. I got a good deal.

Ethiopia began as a shock when driving went back to the right side. It should have been a relief, but it just confused me all the more for a day or so. I had talked to a few people about what to expect cycling highways in rural Ethiopia and all said I’d see lots of excited children, but would be pretty much out of the pastoral culture of northern Kenya. So, I decided to ride the bike again. Camping was about impossible as you go from a comparatively empty desert to crowded foothills and highlands. Hotels, however, were cheap. I lasted three days but was back on a bus at Hagere Mariyam. In part I was skipping a 200 mile stretch of rough dirt road that would be hilly and slow, but I knew as well the kids would be unrelenting. From the border to Hagere, about 200 miles as well, I had rocks thrown at me, one kid hit me with a stick, one karate kicked at the pannier as I went by, many chased and grabbed at anything loose- usually a bag of garbage or a half empty bottle of coke under a bungi. Probably the most disturbing was a little girl no more than three or four years old shaking her fist at me.

Two busses and one van ride, over two days, got me to Modjo, Ethiopia and a far easier culture to be in. Kids were in school again, adults had work to do. I stayed in one of the nicer hotels of the trip in Modjo for about $20. From there I cycled the remaining 45 miles to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capitol, where I met with Haile-Kiros Gessesse. Haile is an old friend of one of my friends in the US, Gail Blattenberger, and she hooked me up. Haile took me to dinner that night with a few friends that I soon realized were some of Ethiopia’s more important people. Haile, retired now, was Ethiopia’s Ambassodor to China and held several government positions over his career. He was part of the Ethiopian revolution that, in 1991, overthrew a government, led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, responsible for a genocide over the previous fifteen years that claimed over a half-million lives. The Red Terror, or Qey Shibir was the height of it in the late 1970s. War crippled the country’s agriculture and food shortages, exacerbated by drought, led to famine. The famine made Western news, the famine’s cause, war, not so much. Live Aid, two concurrent rock concerts held in the US and Britain in 1985, raised relief money for the famine. Though over $100 million was made directly and indirectly, it’s debated to this day how much of it went to fuel the civil war. After the overthrow, Mengistu escaped the country and is today living in asylum in Zimbabwe, following a similar path with Chili’s Pinochet.

Present at the dinner was Tefera Ghedamu, a journalist and documentary film maker, who also hosts a weekly television show interviewing people from all walks of life with interesting stories to tell. A few days later I was on his show, Meet EBC, which he’s done for over 20 years.

There were a few errands to do over the days spent in Addis and many miles on the bike running around the city. I was lost about half the time and at one place asked a guy, Tekalng (Tek) Assefa, in a parking lot for instructions. He told me what I needed to know as he looked the bike over and then mentioned he was in a cycling club. He said they were doing a ride the following Sunday and invited me to come. Haile mentioned that I should get in touch with the cycling club, there’s only one that I know of, so this was all serendipity. I took him up on it and came to the coffee shop where everyone met early Sunday. These guys are serious riders and go at a much faster pace than I’m used to, but with the bags off the bike I could at least keep up with most (not all!). It was about a 50 mile day that left me as tired as having ridden a 100 mile day at the regular pace. I had a great time though and Tek paid for breakfast and a lunch he wasn’t even able to stay around for.

I met Gene Lin on the ride and he invited me to stay at his place the last night in Addis. Gene is from Vail, Colorado and is a consultant to the Ethiopian government working on upgrading electric infrastructure. Gene was a great host, fantastic guitarist and wouldn’t let me pay for anything. He took me to a wedding reception at the home of Norway’s Ambassodor to Ethiopia, providing me with appropriate attire. During the reception the Ambassador gave a speech that ended with the fact that we all come from Africa and have a very recent common ancestry. I was impressed.

From Addis Ababa I had intended to carry on to Eritrea, cross the Red Sea to Yemen and on to Oman. On the grand map of the Eastern Hemispere, Yemen and Oman are the “Pythagorean cutoff” from Africa to Asia. The objective from northern Africa is to get to Asia without going through Iran, where I wouldn’t be admitted anyway. If I got to Oman I could take a boat or fly from Muscat across to India. Nobody I talked to had much to recommend in Eritrea, a heavily industrialized place known as a refueling stop for a steady stream of ships going to and from the Suez Canal. Yemen is in the midst of a civil war and would be hard to get into. Oman, by contrast, is safe and has a thriving economy. Oman was first recommended to me by my friend Daniel Steuri back in Patagonia. Addis has regular flights to Dubai in The United Arab Emirates (UAE), which borders Oman, so I booked a flight to there, with the intention of cycling Oman’s northern coast to Muscat, the capitol. The only downside is the season- HOT.

The ride through Oman has been good overall. People are friendly and I can leave the bike unattended about anywhere. For the first time since leaving the US, I’m encountering large grocery stores without armed guards covering the entrances. Some places in Argentina had things dwindled to a guy in a uniform and no visible firearm, but about anywhere else you were greeted with sawed off shotguns and AK-47s. Of course, these same guys were also watching the bike so I couldn’t complain. (Ethiopia is the one place where a security guard and an accomplice at a restaurant tried to steal the bike’s front pack- another story).

The heat is intense here and walking out of an airconditioned restaurant into it will part your hair. It’s dry heat though and soon you’ll begin to sweat. That’s the key. So long as you’ve got water, and I drink gallons of it a day, it’s down the hatch and out your pores in a coninuous flow to keep clothing soaked; cotton works best. On the bike, you try not to be in a hurry and if movements are kept slow the light breeze you create riding makes it surprisingly tolerable. Days have been over 110°F and nights get down to about 95°F.

It took five days to get to Muscat and I was able to camp throughout on some incredible but desolate desert. A terrible beauty. At the moment I’m jumping through hoops trying to get a visa to India and I’ve been nearly a week waiting on it. Hotels are expensive here so I’ll be glad to get going again. There are no alcohol sales in Oman (except at the airport) so I’ve involuntarily saved money in that regard. It’s too hot for wine but a cold beer would sure be nice.

Once in India, I’m not sure what’s going to happen. Not too much interest for folks making the ride over Tibet, and the price just keeps going up. The Nepali-Sino border has been closed from a 2015 earthquake but was supposed to reopen this year. Now land slides will keep it closed till at least next year, meaning one would have to fly to Lhasa and then begin the overland trip. I’m looking at the moment at Pakistan again and possibly taking the Karakoram Highway which would lead to circumventing Tibet’s west side and then on to Mongolia by a different route. On the upside, I’ve got the whole season to get to Ulaanbaatar, which from India is far less distance than that covered last summer in South America. The unknowns, however, are far greater. Visas are getting harder, borders uncertain. I was hoping to winter in Ulaanbaatar and then start on Siberia as soon as melting snows would allow travel in the spring of 2018. Latin America, from Mexico on, is for the most part friendly but I know now that the rest of the world doesn’t necessarily follow suit. Till next time.