September 12th, 2017

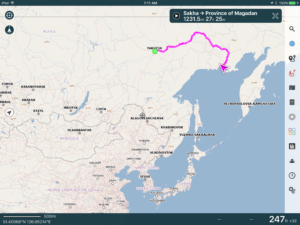

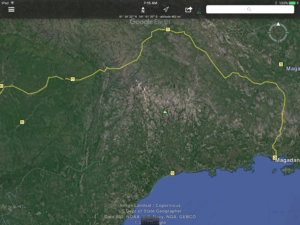

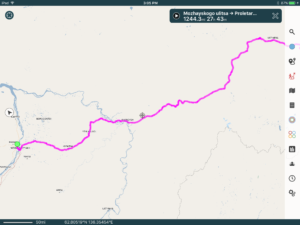

The Kolyma Highway is the world’s longest federally funded dirt road. It covers about 1200 miles, nearly the distance in going from Denver to San Francisco, with about 1100 of it being dirt/gravel. It’s by far the toughest piece road I’ve encountered in 23,000 miles of cycling since leaving Logan. It took 21 days and all else till now was just training. Mosquitos and flies could be horrendous. Some stretches I wouldn’t see a vehicle for hours and others would have a steady stream of trucks throwing up either choking dust or mud-spray as weather dictated. There were many steep grades and passes. Towns were few, with one stretch of nearly 400 miles having only a shack selling gas at the half-way point. Bears closely related to our grizzly are said to be plentiful but I saw only tracks.

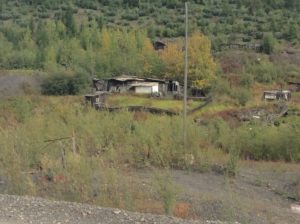

The Kolyma (CALL-ah-mah) was built largely by Russian convicts and prisoners of war for the extraction of gold and other metals on the Kolyma River. Beginning in the 1930s, is was a Joseph Stalin project put in coordination NKVD’s Dalstroy, a USSR forced-labor program. NKVD was the predesessor to the KGB. The Dalstroy had a reputation for brutality and unknown thousands, perhaps over a million, perished in the GULAGs. Records are scant. The Kolyma today is called The Road of Bones as surrounding permafrost made the road itself the easiest way to dispose of bodies. Efforts for getting gold were stepped up during WWII to help fund the war. With millions dying in the fight against Hitler, prisoners, many of which were POWs, on the Kolyma were dispensable. GULAG commendants themselves were several times executed for not getting enough work out of the inmates. Stalin is known to have said that a prisoner was only good for about three months and after that they didn’t need him- he was just another mouth to feed. The inhumane GULAG conditions died with Stalin but intensive gold mining goes on today. Since Perestroika, investment and mining technology have come here from worldwide sources including the US and Canada.

Magadan has grown to a city of over 100,000 people and is a major port and jumping off point for the gold fields. It was a “closed city” till 1987, the beginning of Perestroika, and even a Russian needed an invitation to go there. Tourists worldwide now come here as well as Russians looking for jobs and better pay. There has been boom-bust over the years with fluctuating metals markets and recovery from the dissolution of the Soviet Union was slow. Today, Magadan Oblast has much the same allure and culture that Alaska has for the US. It’s remarkably similar to Alaska in climate and topography, with the two being symmetrically situated about the northern Pacific Rim. Any Russian you talk to is well aware that Alaska once belonged to Russia, a fact that often gets squeezed into conversations.

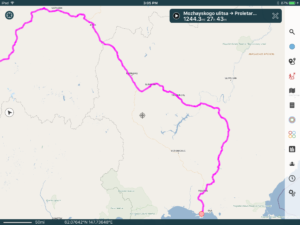

The Kolyma begins in flat terrain and travels 200 miles through swampy taiga to the Alden River where a ferry transports vehicles across to Khandyga, the last city of any size (7000 people) for 400 miles. There’s one cafe at about 60 miles out, a shack selling gas at 200 miles and then the town of Ust-Nera at 400 miles. Ust-Nera marks the half-way point of the Kolyma.

Soon after Khandyga the road left the flats and entered mountains. These were the first real mountains encountered since Mongolia and were a welcome change. Flowing water was everywhere and it was great to be able to dip your water bottle in to a stream to get a drink and then not need to carry more than a few swallows-worth of extra weight. The mountains meant steep grades and rougher roads that were made from sharper, crushed gravel causing many flats. Being on a thin-tired road bike, I was worried from the beginning about this much dirt road but was relieved when I had had no flats the first five days. Then the rougher road bed, sometimes with gravel a couple of inches across (‘2-inch minus’ in American lingo) would pinch the tire against the rim if you caught one just right and puncture the tube leaving a pair of “viper bites”. It’s tough to patch the two holes with one patch, and sometimes it takes two. After a few days of two-flats-a-day it was clear I wouldn’t have enough patches to get another 800 miles to Magadan.

Vehicles and trucks have the same problems with these stretches and the shoulders are strewn with old tires and tubes. With few tire shops the entire length of the Kolyma, changing a tire often meant removing it from the rim right at the roadside and repairing it if you could. Semis are equipped with air compressors to refill the tire. Tires and tubes beyond repair line the road. But the old tubes came in handy for me. I was able to cut a strip out of one to make a liner for the inside of the rear tire. This gave a little added cushion. It helped things, but I was still getting a flat maybe every other day.

As I got close to Ust-Nera I decided to try another idea. I had had it in mind for a while to completely stuff the tire with thin strips of rubber from the old tubes and make it into a “non-pneumatic”. It being better to experiment when getting close to a town as opposed to when starting off on a long empty stretch, I tried it out maybe 80 miles from Ust-Nera. It worked tolerably well. On the dirt roads I could hardly tell it from a pneumatic, though later on when I hit pavement it made for a rough ride. I made some adjustments over the next couple of days to get it running as true as possible and ended up riding non-pneumatic on the rear 700 miles to Magadan. In that time I only had one flat on the front, but it was simply that the tire was shot and I had a new spare to put on.

The road to Tomtor is the original Road of Bones and shorter than the loop to Ust-Nera by about 120 miles. It’s unmaintained and I didn’t dare try it on the road bike but I got word that two Canadians, Kara and Brandon, came from Magadan across it while I looped up to Ust-Hera. The R of B is a small world and we were put in touch with each other later on and have exchanged a few emails. Tomtor and twin city Oymykon claim the world’s coldest recorded temperatures (-71 C) for cities outside of Antarctica.

The mix of people in remote towns like Ust-Nera range wildly from almost hostile to over-the-top friendly and little in between. Alcoholism and associated domestic violence are ongoing problems. I was approached by drunks on several occasions that would at first be very friendly- especially when they found I was American- but you never knew where it was heading. I had a couple of times, 250 pound drunk men put their arm around me and start walking towards some untold destination and breaking away without an outright confrontation could be tricky. They were insisting on hospitality and to refuse was to offend. In Ust-Nera I wanted to buy more patch glue from a “shinomontaj” (tire repair) but was getting that sort of treatment from people working there. I managed to break free, sans patch glue, but decided after that to just get to a grocery store, stock up for the next week, buy gasoline for the cook stove and get out of town. I got the gas, found a magazine productivy (small grocery store) and was packing to go when a guy, Nicoli, I had said a few words to in the store was watching me pack and asked some questions. He spoke a few words of English, was sober and respectful- you never know whether you’re going to get sincere curiosity or heckling curiosity. After a few minutes he invited me to stay the night at his apartment which he shares with his mother. Well, they treated me like royalty and I ended up staying two nights and got a much needed rest. It was one of those times you could really use some kings-x safety and there it was.

J6

J6

A few miles out of Ust-Nera I passed the half-way marker for the Kolyma. The first half took 10 days so I was making excellent time thus far. It was August 20th and it looked like I could make Magadan by the beginning of September. Before Yakutsk I was thinking I might average 40 to 50 miles a day on the dirt-road Kolyma. That would have put me in Magadan more like mid September. I was dreading what would happen if things went even slower, as they usually do. Ust-Nera is at 64.5º north- the Arctic Circle is at 66.5º – and the end of September is essentially late fall / early winter. But I was averaging over 60 miles a day and though the rear tire was slowing me up a bit, I knew I’d make it OK.

B

B

For the last couple of days getting to Magadan the weather turned rainy and cold. Magadan’s airport is at Sokol, about 40 miles before Magadan, and I got there in driving rain and found a hotel. Later that night I got a knock on the door from two guys, Dima and Sanya I (Sanya II to be met later and there was even a Sanya III) who knew I was coming and somehow learned I was in that hotel. Sanya spoke enough English that we could communicate and soon I was invited to a gathering in Magadan the following night. Dima picked me up the next afternoon and shuttled me to town. Dima took me all over, wanted to pay for repairs to the bike and payed for a room. Their gathering was a great time with food cooked over a fire, guitars and singing later on. There was no alcohol- they call themselves “the new Russians”- for which one can only have respect. These folks have got it figured out.

The next day they had a mountain bike ride planned and Dima lent me a bike as mine was pretty much non-functional with the front rim wear and a freewheel pawl that had begun to skip. We rode 12 miles of road/trail to an oceanside cabin at Cape Ostrovnoi and spent the night. Next day Sanya I and I hiked to Cape Ostrovnoi and got beautiful views of rugged coastline and saw many sea birds and chuleen, or seals.

So, I’ve rented an apartment for a month and will stay and get to know Magadan a little and learn some Russian. I’ve bought a cheap guitar to play and Dima has lent me another guitar. I’ve been playing a lot and learning a few Russian folk songs but old tendonitis problems in my wrist and arm have been right there to haunt me. After this, there’s not much left but to make my way back to the US. I’m less than 800 miles from Alaska’s Aleutian Islands (Attu) but so far I haven’t found direct transportation there from Magadan at any kind of reasonable price. The alternative is an inexpensive flight to Vladivostok, ferry or fly to either Japan or South Korea, then probably fly to San Francisco. Then it’s either to Anchorage for the winter or cycle home for house repairs and earning money for the first time in a while. At the moment I’m favoring the latter and would do the logistically easy leg from Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay next spring/summer. Continue reading Yakutsk to Magadan