September 10th, 2016

Well, I’ve made it to Peru after longer than intended travel through Ecuador. Not only does the mountainous terrain there make for low mileage days but the zig-zagging roads make progress towards the southern tip of the continent just about grind to a halt. The lack of progress really went unnoticed though, because it’s all very beautiful and continually interesting. The time slips away and overall seems to pass more quickly now then when I started out over five months ago. Several days were spent hiking two volcanos near Quito as acclimation for climbing Chimborazo, Ecuador’s highest point at 20,400 feet, then more days for a failed attempt on the mountain itself. On top of everything I’ve lost days to illnesses for which I have no explanation except mild food poisoning. Chicken is a Latin American mainstay- they eat it breakfast, lunch and dinner- and in Ecuador it will come with a meal whether you specifically order it or not. Biting into it and finding the meat not thru-cooked always leaves you wondering what the next week will bring.

From the hostel in Fuch’s Plaza in Quito I found a nearby outdoor shop that rented gear and functioned as what appeared to be a brokerage for guide services. Three or four years ago the Ecuadorian gov’t declared that its main summits can only be climbed with a guide. At the surface, the reasoning is safety related- the volcanos are subject to rockfall and avalanches for which there have been a few fatalities over the years- but I doubt they overlooked revenues and job creation. At the outdoor shop I tried to get a feel for what the policies were and how strict the enforcement. The owner at this particular shop was of course eager to sign me up and didn’t seem to care what kind of shape I was in. I told him I needed to acclimate first and his response was that he could provide a guide for that too. I said I’d get back to him.

I needed at some point to replace the camp stove I had lost way back in Mazatlán and the shop at Fuch’s plaza had a few. They were mostly butane canister type and though light weight and easy to use, required fuel canisters that are not readily available. I was looking to purchase another MSR Whisperlite, like the one I lost, or one that burned kerosine or diesel. The Whisperlite burned white gas, but ordinary gasoline would do in a pinch, and they can be jetted for diesel. Well, it turned out he had one stove there that would burn gasoline- it was a primus. Swedish-invented primuses are wonderful stoves, last indefinitely and can burn ordinary gasoline. They’re what I grew up with- my dad bought me a Svea (primus being the type, Svea the brand variation) in the early 1970’s that I used for many years. Aside from the fact that they stink (from an olfactory point of view) and are cumbersome to use, they’re heavy. The model he had for sale, similar to what we would have called an Optimus, was especially heavy because of the case it came with. These stoves are almost completely obsolete now in the U.S. and I’ve picked Sveas up at garage sales and thrift stores for just a few dollars in recent years. A couple occupy basement shelves at home where I’m wondering if Smithsonian might one day be interested in them. Even Whisperlites are becoming hard to find from retailers as the world seems to want the convenience of canisters. Well, this dinosaur was going for an obscene $100 but I went for the bird in hand. In retrospect I would have done better to order what I really wanted on the Internet (eBay) and waiting for delivery in a place conducive to hanging out for a few days……like Fuch’s Plaza. After paying $114 with tax I left with that sinking feeling of having been suckered.

The next day, without knowing what I was going to do about the “guide question”, I set out to climb Pichincha, a 15,700 foot peak near Quito. To get to it involved riding the bike first over a 12,000 foot pass, then dropping 1500 feet to the town of Lloa (‘yo-a) and then up dirt roads to as far as I could reasonably take the bike. A 4×4 track leads to a hut at over 14,000 feet, but I locked the bike to a fence post at about 12,000 feet. The majority of my gear was left at the hotel at Fuch’s Plaza, so I as traveling light.

Pichincha erupted as recently as 2002 covering the town of Lloa in ash. Technically it has since been illegal to go to it’s top or into the crator, but warning signs were obviously being ignored. I had a beautiful hike over blocky pinnacles and surprisingly solid rock to the summit. Views to the west were a sea of clouds over the Pacific. To the east it was just the opposite, the high peaks of Cotopaxi and Cayambe hidden in clouds but surrounded by xeric plains of rain shadow. It was a long day, the most exciting of it finding my way back to the hotel through five or so miles of Quito’s labyrinth of streets after dark.

The next peak in the acclimation process was Iliniza which lay to the south. I left the Quito hostel and took the main highway for 30 miles to a turn off on an outlandishly bumpy cobblestone road that I had to walk the bike for much of. After 5 miles I found a good camp site close to the foot of Iliniza. Iliniza is on Ecuador’s list of “major peaks” and therefore required a guide, so I was keeping a low profile and camped out of sight in some pines. I got a 4 am start to hike Iliniza Norte, the lower of the volcano’s twin summits at just under 17,000 feet. I hiked the remaining road to a trail head and then on to just short of a permanently occupied refugio at about 15,000 feet. Nearing the hut shortly after day break, I noticed a trail leading to the right that appeared to be a bypass and, in a game of cat-and-mouse with the park people, took it. This turned out to be the main path the the north summit and I had a beautiful hike to it, all to myself. Way towards the bottom on the descent I encountered someone who appeared official and asked where I’d been but I just shrugged and told him I’d been a couple of kilometers up the trail.

I spent another night in the secluded campsite and bounced back down the cobblestone the next morning. After a long day of relentless grades on the main highway to the south I threw down that evening, just at dark, on a less-than-ideal camp that overlooked some houses. Kids were playing games in a lighted, dirt street below but they could see me up there when I walked around and soon were all staring up at me. I tried to just ignore it and only wanted to get some sleep. Well, soon the father and mother, led by about ten children, climbed up the hill in the dark to see what I was about. After a minute or so of broken conversation, and seeing the bike a gear strewn about, the mother was insisting that I come down and stay with them! I explained I was “muy cansado” (very tired) and just wanted to get some sleep. The father understood perfectly and they thankfully left me alone. End of story, except for the next morning when one of the children, Anderson Caiza, brought me a two-litre bottle of water and helped hold the bike while I packed it.

In one of the towns I passed I noticed a leather/saddlery shop that had a bolt of vinyl coated nylon visible near the entrance. This is the stuff climber’s haul bags and river bags are made of- really tough, waterproof material. The orange bag that I lay on top of the panniers was worn out to begin with (actually it was a bag that belonged to my dad) and was now pretty much a few tatters encasing a plastic garbage bag. I had these guys sew me up a new one, using the old bag as a pattern. It worked well enough, the price was right, $15, but one small problem in that the drawstring wouldn’t cinch the end closed on the much stiffer material. Oh well, I’d think about it and make modifications later. I moved on to the town of Ambato and the turnoff to go to Chimborazo. Dropping into town (Ambato is in an uncircumventable hole- it’s all the way down and all the way back up again) I noticed another sewing shop with more nylon-reinforced vinyl. The lady there made a flap for the bag to close it up and now I have a very good, waterproof sack for the sleeping bag and clothing. I also bought a yard or so more material that I’ll at some point replace the already deteriorating denim pannier I made back in Mexico.

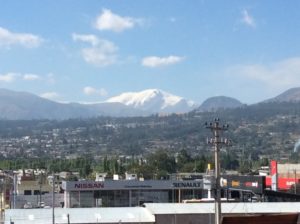

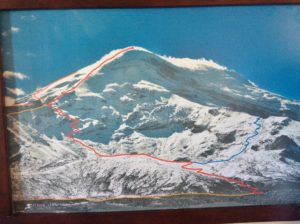

Leaving Ambato, I started up grades towards the refugios on Chimborazo. In two more days I went from 8000 feet to nearly 16,000 feet on the bike and was in an alpine world of sparse vegetation, rock, vicuñas and snow flurries. The lower refugio, Carrel Hut, had a good restaurant for reasonable prices and is where guided trips up the mountain are organized. One of the guides there first quoted me a price to climb Chimbo of $280, consistent with what I was told at the sports shop in Quito, but then upped it to $380 later that afternoon. I said I’d think about it, but then lost a day to being sick, probably from eating my own 3-day old leftovers from chicken that may have been tainted to begin with. Two days later I felt better and, though not 100%, took a walk in thick fog up to the next hut, Whymper, at 16,400 feet. I felt OK at Whymper, walked a little more and ended up pounding out hands-in-your-pockets trail to about 18,500 feet and near to where glacier travel begins. Seeing this much of the mountain and the remaining snow slog, the $380 didn’t seem worth it for what was essentially boot/ ice ax/ crampon rental.

Returning to Carrel, the guide then quoted me $200, but I needed to confirm it with the manager of the huts when he arrived later that morning. For $200 I was again considering it, but when the manager arrived he upped it back to $280 and expressed displeasure that I went as far as I did up the mountain. I had had enough at that point and packed up to go.

One aside about Chimborazo is that relative to the center of the Earth, it’s the world’s highest mountain due to the equatorial bulge caused by centripetal forces of the spinning planet. It’s a contrived sort of statistic, but a draw for people wanting to climb it and one can see an impetus for commodification- if they can make a buck off it, they will. I should mention also that the oblate geometry also makes the mouth of the Mississippi River “higher” than its headwaters. As an excersize to the reader (many of whom I know can answer it), tell me why the Mississippi doesn’t flow the other way!

So, it was back down to about 10,000 feet and the city of Riobamba where I needed to attend to another important bicycle repair that came to my attention just before getting to Chimborazo. It seems the front forks became loose and began vibrating when I put the brakes on. Usually this means the headset bearings need tightening or replacing. On closer inspection I could see that the braze (weld) where the steering tube attaches to the fork crown had failed- the cobblestone road at Iliniza was the last straw. It really couldn’t come completely apart because the bolt & nut stem attaching the front brake locked the two pieces together. I couldn’t otherwise see any signs of cracking or deformation. It had to be repaired though, regardless. I was trying to imagine the best way to do it and finding some used forks was one option. If I were at home it would have been simple; re-braze the joint. Here, I needed to find both someone with an oxy-acetylene torch and the necessary skill to make the braze. Either that or somebody with an oxy-acetylene torch willing to let me do the braze for a price.

The fork crown- steering tube braze is probably about the trickiest joint in frame building. Among a few possibilities, brass brazing rod is the weld material generally used and I figured- hoped- it was common here along with the accompanying flux that allows the molten metal to flow. It all works similar joining copper plumbing fittings, but far less straightforward or user friendly. Temperatures are critical. The steel is “Colombus SL” (actually SLX- the latest and greatest circa 1980) and is an Italian chromium-molybdenum steel comparable to American 4140. If the steel gets too hot though it becomes brittle and is subject to cracking. In making a braze, molten brass travels to where the steel is the hottest and controlling it in the fork crown is especially tricky because of differences in the thickness of the steel- it’s easy make thin places hot, difficult to make thick places hotter than the thin places and woe is thee should a thin place get too hot.

After knocking on a few more-or-less unfriendly doors, I found a mechanic’s shop that was willing to “rent” his torch, and also had on hand a stick of brass rod and flux. After removing the forks from the bike and taking the brake stem out, the steering tube and crown could be pulled apart for cleaning. I could then inspect the joint and realized that I had only “tacked” the two together and never came back to fully braze it. Well, the “tack” lasted 35 years! The re-braze was a challenge; a little kid tripped over the torch hoses and knocked the forks down while I was brazing, and then the acetylene ran out. I told the owner I was out of gas and he said he’d be back in five minutes with more. As a little background and at the risk of boring everyone with all this technical stuff, Ecuadorian oxy-acetylene outfits use an oxygen bottle just like ours. The acetylene, however; comes from these ungainly tanks that look a little like potbelly stoves. I didn’t get a picture of one but if I again get the opportunity, I will. How he was going to exchange this massive tank with another in “cinco minutos” was beyond me, but I was hopeful. Sure enough, in five minutes he returned, not with another tank, but with what appeared to be a small plastic bag containing some rocks. He unbolted a swinging door low down on the tank, threw some rocks in, sealed it up, and voilà, I had gas again. I didn’t waste his time asking stupid questions, but did do some research when I got to a hotel later that night. Acetylene gas was traditionally made by heating calcium carbonate (limestone) in a kiln to make calcium carbide which can then be reacted with water to make acetylene gas in a ridiculously simple stoichiometry. In the past it was used to light everything from gas street lamps to coal miner’s carbide headlamps- cavers still use them today. (They went out of style in coal mines when it was discovered the lamps could ignite methane gas). How safe these welding tanks are I have no idea, but it’s how they do it in Ecuador.

With the forks brazed I reassembled the bike, but with no fine tuning adjustments, and went in search of a hotel. It was by then after dark and it took a while to find one. The next morning I took it all apart again and did some hand filing to get the headset race to seat properly and then hit it with spray paint. Between working on that and another round of illness, I spent three nights at the hotel. In that time, amazingly, I got to know the girl working the front desk a little and by the last day she had proposed marriage, and was willing to pay a price for it. She was a music student trying to get into a university in the U.S. and wanted citizenship. I answered by holding my wrists up in the manner of when being handcuffed.

I left Riobamba still not feeing 100% and got less than 10 uphill miles to Cajabamba, and checked into another hotel. Next day I felt pretty normal again and did another day of uphill and then descended, finally, onto the Pacific side and into all those clouds I had been getting glimpses of ever since the rainshadows of Colombia. That first afternoon the fog was thick enough that I quit early when I saw a public lands-type sign indicating a side road to a waterfall. A two kilometer descent down a dirt road led to San Rafael Cascada and a beautiful, if out of the way, camp. The next day’s descent spit me out onto coastal plains and jungle. I had dropped from 12,500 feet to about 800 feet in less than 40 miles.

After egressing the mountains there was nothing ahead but straight, flat, windless terrain that might be considered boring but here it was a welcome relief. I did back-to-back 90 mile days, had an easy border crossing into Peru (the place was practically vacated), and now I’m in Tumbes, Peru only a few miles from the coast. In a few days time I’ve gone from treeless páramo, to jungle, to desert scrub and now, almost without warning, the terrain is becoming pure desert. I’m anticipating Atacama-like desert sand within the next few days. Tomorrow I’ll have about a 10 mile ride to the coast proper, and am looking forward to a hundred or so miles of highway right on the ocean.